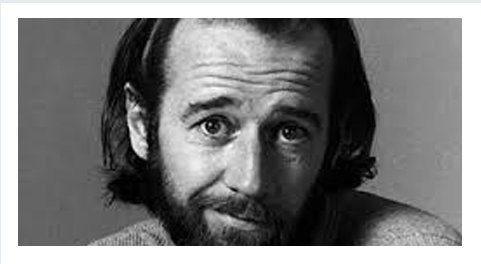

“Have you ever noticed that anyone driving slower than you is an idiot, and anyone going faster than you is a maniac!” — George Carlin

Everyone has an opinion and no one can agree on just about anything. Animated debates on CNN…. opposition parties within the halls of Congress… hostility between the president and the media… ridiculous sniping in social media… and on and on. Differing opinions are a good thing, but at some point you need to convert opinions into an actionable solution, whether you’re running the federal government or a marketing department.

How can you get everyone to agree?

It’s easy to make a final decision when everyone agrees. Unfortunately this rarely happens. But perhaps the question we need to ask is this: why do we need everyone to agree? When it comes to a new design, promotion, or campaign for a company, the people in charge seek out other opinions to bolster their decision. And yet if that same company were looking into a new business deal, I doubt the CEO would be asking employees’ opinions about whether or not to make the deal. And the reason is simple — people don’t have the information and experience necessary to render an informed opinion. The same is true in marketing, and making a final decision based on consensus can lead to a bad decision, or at least an ineffectual one.

Let’s say you’re part of a group that is reviewing concepts for a new advertising campaign. Everyone has an opinion, and everyone thinks theirs is the right one. The debate rages on, and finally, in an effort to end the arguing and form a consensus, the group institutes the tried-and-true method of ranking the concepts. The concepts that people either love or hate are cast aside, leaving the one that’s middle-of-the-road — not offensive, but not exactly memorable — as the winner. But why aren’t people excited by the decision? It’s because it’s a compromise. It’s as if you’ve gotten all the maniacs and idiots to drive down the highway at the same speed, with no one standing out. While this may be safer in the real world, in the world of marketing, safe really means dull. So, unless you have a hard time making decisions or need a scapegoat if things go south, make the decision yourself or keep the decision-making to a small group of trusted stakeholders.

A lesson from the NBA

For many companies, budget dollars and marketing opportunities are relatively limited, so decision-making and risk aversion go hand-in-hand. It also leads to the urge to go with safer solutions.

But we can take a lesson from the NBA as to why, ultimately, this might not be the most effective course of action. When the NBA first introduced the three-point shot, players didn’t shoot it that often. The logic at the time was that gaining just one more point for a shot that had much less chance of going in wasn’t worth it compared to an easier, higher-percentage two-pointer. But once the data was analyzed, teams realized that even though the three-pointer had a much lower success rate (around 35%), teams still scored more per game than they did just shooting two’s (around 50%). The focus changed — they went with what would ultimately help them win, and not necessarily what was the safer, more reliable approach.

We need to stop looking for safe solutions that everyone can agree on but no one is excited about, and instead embrace bolder ideas that generate strong opinions. I’m not advocating campaigns that intentionally create a negative response, but too often, bold ideas are rejected because of the strong emotions they kick up — even if some of the responses are very positive. Rather than dismissing them out of hand, we should be asking these questions:

• Did it get people thinking?

• Can the idea be made to work?

• Will it meet the objectives?

• Is it true to the brand?

Pushing bolder ideas through

When a person has a negative reaction to an idea, they tend to harden against it rather than really listen. That’s a shame because sometimes new ideas, even those that seem counterintuitive, are just what’s needed. As an example, imagine floating the idea that homelessness can be eliminated by providing homes to those without one. Sounds crazy, and completely unaffordable. But this is exactly what Utah did. They did a study and found that the annual cost for ER visits and serving jail time by homeless people ($16,670) was considerably more expensive than providing an apartment and a social worker ($11,000). Since instituting the idea, they’ve reduced homelessness by 78 percent while saving taxpayers a considerable amount of money.

One way to stop the quick negative reaction is by applying a simple rule: when an idea is presented, no one is allowed to react by beginning a sentence with “I don’t like it….”, or “it won’t work because…..” Take likes and dislikes off the table and instead ask people to evaluate an idea solely on how it might work or how effectively it achieves the objective. People can offer suggestions or ask questions, but they need to be shaped in a way that promote a constructive discussion and not add roadblocks. For example:

Bad: We don’t have the money to do this.

Good: How can we fund this?

Here’s another rule that should be applied: while ideas are being developed, don’t ask the opinion of anyone who is not familiar with the objectives and issues surrounding what you’re trying to accomplish. Random people around the office or friends can only answer based on their personal likes or dislikes, which may not be relevant. The only exception to this rule is if you are using focus groups. Focus groups are comprised of a specifically selected group of people who are asked specific questions to see how your target audience will react. And once you get close to a final solution, you can ask people their opinion — just to make sure there isn’t something objectionable, misleading, or confusing that you might have missed.

This is my opinion on the matter. Let me know if you agree. And if you think I’m an idiot or a maniac, you can keep your opinion to yourself.